Project Description

Las Ideales 2012. (Tribute to the ‘cigarreras’, the female tobacco workers.) With music of Leopoldo Amigo.

WATCH VIDEO:

THEY DANCE STILL IN THE NEBULOUS GLOW OF MEMORY

The idea that Monique Bastiaans had originally conceived for the installation was completely different from the project that is now presented in the Las Cigarreras exhibition hall. This project had been slowly brewing for a few years, and we had been looking forward to presenting in Alicante. Still, the place ultimately selected for the exhibition changed it all.

Bastiaans is always very mindful of the place where she is going to exhibit her work, of the space or environment that is going to hold it. She usually develops each project for a specific site, taking into consideration the particular characteristics of the place, be it an exhibition room or an outdoor location, whether the setting is urban or in the middle of nature, the latter being the settings she favours most. She seeks to integrate her pieces into their surrounding environs and hopes to generate something beyond a mere dialogue, a relationship which, almost for a question of necessity, calls for an intimate engagement.

In her practice, artwork and environment interact in varying degrees. The interaction takes place on many different levels: space, light, material, colour, sound, and even smell. It can take subtle forms, as happens with the movement of the breeze and the reflected sunlight in the nylon nets of Mediodía se celebra en el interior (Noon Takes Place Inside), from 2001, or, for instance, by emphasising the clash between synthetic materials and organic forms, as in the case of her exhibition from 2007 called Vecinos verticales (Vertical Neighbours). At any rate, she always respects the essence of the emplacement.

“Who am I to torture some trees and presume that the result will be an improvement on what used to be there before?”1 she wondered in Ribarroja del Turia while working on the intervention project Adeu tristesa (Farewell, Sadness), which turned a field of orange trees that had died from citrus tristeza virus into an orchard overflowing with colour and hope, where she had wrapped the trees in red, fuchsia, and crimson fabrics. The respect she feels for the environment also explains one of the main reasons behind the ephemeral character of most of Bastiaans’ work.

The architectural space of the former tobacco factory buildings in Alicante that have yet to be refurbished surprised and captivated Bastiaans from her first visit. On seeing these enormous bays, revealed in the play of light and shadows produced by the sunbeams that filter through the large windows onto the flaking walls, we can conjure up a picture of the working environment during the years when the tobacco factory was in full swing. Still, what truly captivated her imagination in this case was the history of the factory, and particularly of its women workers.

At a time when most women were homemakers or worked in the fields, the factory in Alicante employed as many as five thousand women at a time when the population of the city had just passed the mark of fifty thousand people. The effect of this enormous workforce on the domestic economies of all these families engendered a certain shift in the social and political spheres of the town. The cigarreras, as they were known, had to develop ingenious strategies to reconcile their personal lives with long working hours, which in many cases were prolonged further by lengthy commutes to and from home. They organised themselves to tend to meals and to the sick, and more generally to develop a sense of community within the factory; they even set up a school to care for the children of those women who did not have any family members to leave them with. The strong solidarity and unity with which they faced various adversities encouraged the development of a unionising and activist spirit that set the foundations of the feminist movement in the town, and left an emotional mark in the memory of the people of Alicante.

The collective memory tends to be positive and enthusiastic, especially after the recent institutional refurbishment of the property for its public use. We can all generally agree that it is fitting to use the building for cultural uses, not only because it fulfils the appropriate architectural requirements for such purposes, but also because, historically speaking, it was the source of a series of social stirrings tied to ideals of progress and culture that few of us question today. But despite a number of recently published studies, this popular memory is also vague and imprecise, overlooking, for instance, the dire working conditions of the different periods of the factory’s activity, and focusing on the social achievements of the cigarreras.

As memories form it is not unusual for them to be slightly warped. Some facts are magnified, and it is only natural that other events are ignored; objective readings are left out of the record, they are of little interest. Furthermore, the influence of potential emotional charges of all kinds on the process of construction of memory invites a comparison with the processes of mythification, where language is used allegorically and incongruence is camouflaged as paradox. As time goes by, the deformation can change it beyond recognition.2

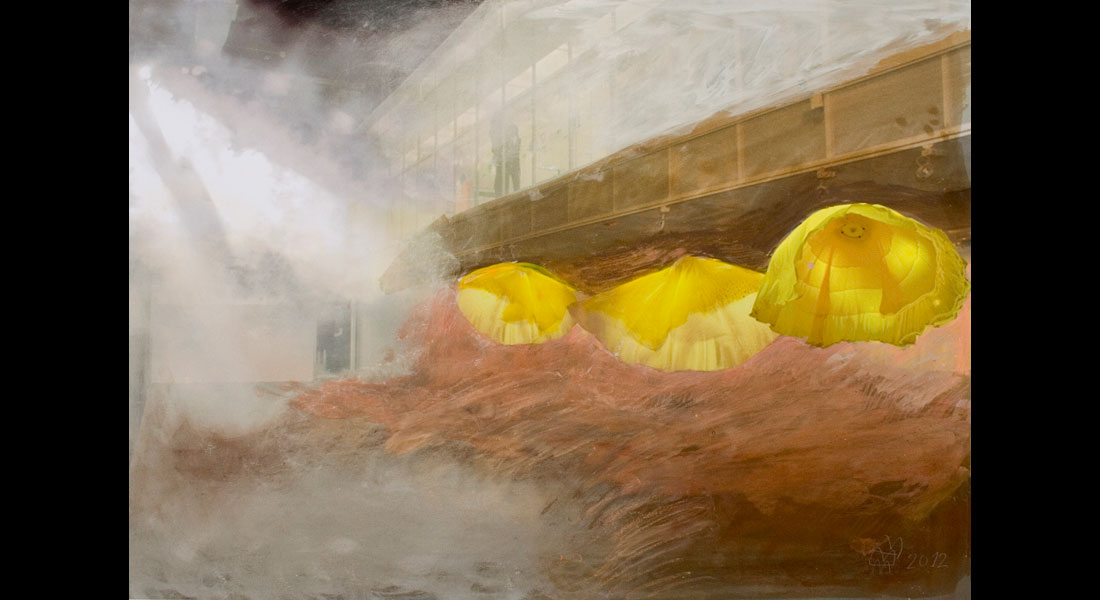

As an homage to the achievements of the cigarreras, and above all to the passion still aroused today by the image we have constructed of their fighting spirit, Monique Bastiaans also makes use of an allegorical syntax in her piece. Eschewing precise definitions, she reconstructs the image of that passion through outsized figurations of certain elements that refer to readily assimilated commonalities about working in the factory and the spirit of the cigarreras. Thus, behind the three large figures of the piece Don’t Dream It, Be It (it is not clear whether they are gigantic cigars (ciggaros) or cicadas (ciggaras), or the nymphs-cocoons from which all else will emerge), we come across a dance of flowing bright fabrics, Las ideales (The Ideal Ones), opposite an enormous tray of large cigars titled 1888 as a reference to the first revolt staged by the cigarreras from Alicante. The dim lighting emulates the light of memory and casts beams that cut through a fog which immerses us in the dense atmosphere and insalubrious air of the warehouses, while from some unclear place, as if coming from a distant memory, somewhere between the hum of the fans and the hiss of the smoke machine, we hear something3 that carries echoes of the voices of the cigarreras singing on their way to the factory.

As happens in many of her previous works—from Medusas in the Playa de las Arenas in Valencia in 1996 to the Ombligos mirándose (Navels contemplating each other) from 2008—the three nymphs of Don’t Dream It, Be It play with the tensions generated by the contrast of the organic forms and the synthetic materials. The seeming solidity of the figures from a distance reveals translucent areas when lit from behind, with intense red hues from the thick paste with walnut stain that coats their delicate lace skins. The precarious balance on the ground, dangling from one end, suggests a lightness that contradicts the heaviness implied by their dimension. Mimesis is avoided—it is not important that the figures resemble cigars or cicadas—in order to emphasise aesthetic qualities, which are versatile and capable of imbuing the object with a degree of uncertainty and inducing a sort of perceptual uneasiness. Bastiaans’ intention is not to obscure, though she does seek to awaken the senses; she seeks to trigger doubts and questions: Are the cigarreras in any way related to the cicadas? Were cigars (cigarros) named after their physical resemblance to cicadas (cigarras)?

1888, the fake tray with its oversized cigars—the product of the women’s work—has the same intent; although in this case there is a certain concession to mimesis with the texture of the cardboard material, so similar to the surface of a cigar that, in the end, the artist decided not to wrap the pieces in real tobacco leaves. The twilight created by indirect lighting then creates a trompe-l’oeil effect in relation to the depth of the cigars, which are nothing but semi-spherical heads pasted to the wall. Their scale only adds to the confusion.

Works such as Moony, from 2002, or Hemelzweet, from 2006, show that Bastiaans is interested in the rhythms that emerge from the irregularities in the iteration of spherical or round elements. Serial production is a resource that reinforces the view of the cigarreras as a group, but it also imbues a sense of spirituality to the piece. In any case, in this particular setup, behind the cigar tray she places the sound system for the music that composer Leopoldo Amigo—who has become a regular collaborator in the artist’s projects—recorded expressly for this installation. Once again we are faced with the question: Should we measure the results of the labour of these women with material parameters, or does this labour have spiritual dimensions?

The skirts of Las ideales are a core element in the installation, referring directly to the cigarreras. This is yet another iterated element. She already used it in the 2007 exhibition Plaisir de fleurir at the Sala Parpall— in Valencia, where its swaying movement alluded to the springtime joy of flowers; later on, with slight modifications and under the title of Merrily, it was combined with pieces that looked like high heel shoes or pearl necklaces in the exhibition Lunes, miércoles y por la noche (Monday, Wednesday and At Night) in Carlet, in a specific context that made reference to the sophistication and extravagance of women’s fashions. In both cases, a single unit was exhibited; now five skirts are being grouped together for the first time.

The concept of the group is reinforced by the chromatic homogeneity of the whole, which prevails despite differences in texture, hue, and other qualities of the fabrics. These variations acknowledge the fact that groups are composed of individuals. The fabrics are in varying hues of yellow, a luminous and cheerful colour immediately reminiscent of a proto-unionised workers’ association with feminist leanings that came to be known as “las amarillas” (the yellows)4.

Moved by groups of fans, the billowing of Las ideales recreates the movement of skirts in a dance, and conveys a sense of freedom that probably approximates the one felt by the cigarreras during dances held on special occasions, for which they rehearsed in the courtyards during breaks. In referring to the joy implied in the dances of the workers, Bastiaans elicits an anachronistic and strange sensation in us, a feeling of relaxation and fulfilment in the recognition of the contribution of these cigarreras to the emancipation and freedom of women in society.

All of this might induce us to think that, in fact, Las ideales is Bastiaans’s project that leans the most toward issues of a social or anthropological bent. However, the language employed is not the most appropriate for such purpose, since it restricts the objective scope of a reflection on those areas. The installation is structured according to the same allegorical rhetoric that permeates the construction processes of emotional memory and of identity itself, a primary logic consisting in basic associations of ideas, akin to the relationships of proximity or similarity in primitive magical-mythical thinking. It is a logic that is found in our epistemological core, and therefore almost instinctive. Nevertheless, this logic is complicated with tropes, parallels, opposites, polysemies, paradoxes and other acrobatics of language. Strategies that enable an awareness of emotional communication while addressing the need for cultural sensitivisation.

A multidisciplinary visual language devoted to experimentation that allows broad syntactic registers, and proves efficient and versatile in reflecting the polysemies, paradoxes and non-specificities of the allegorical discourse. It is in this game of establishing relationships, of insinuating them, of simulating them, in the manipulation of the poetics of those things that are revealed through interaction, that we can find the keys to this artist’s aesthetic language.

Boye Llorens Peters

1 Monique Bastiaans: Adeu Tristesa, Ribarroja del Turia, 2000, p. 3

2 While on the topic of these tobacco workers, and in relation to paradoxes, I am reminded of Nietzsche and his statement that work sets one free, and the aberrant use of his phrase in German concentration camps during the war

3 As I write, composer Leopoldo Amigo is putting the finishing touches to the sound recording that will accompany the installation

4 Caridad Valdés Chápuli: La fábrica de Alicante, Alicante, 2011, p. 158